Introduction

Just before the release of version 0.1.5, I focused on documenting the API. I knew I had to use jsdoc so I started adding comments early in the development process.

Documentation

Before going any further with jsdoc, I would like to quickly present my point of view on documentation.

I tend to agree with Uncle Bob's view on documentation meaning that I first focus on making the code clean and, on rare occasions, I put some comments to clarify some non-obvious facts.

Code never lies, comments sometimes do.

This being said, you don't expect developers to read the code to understand which methods they have access to and how to use them. That's why, you need to document the API.

Automation and validation

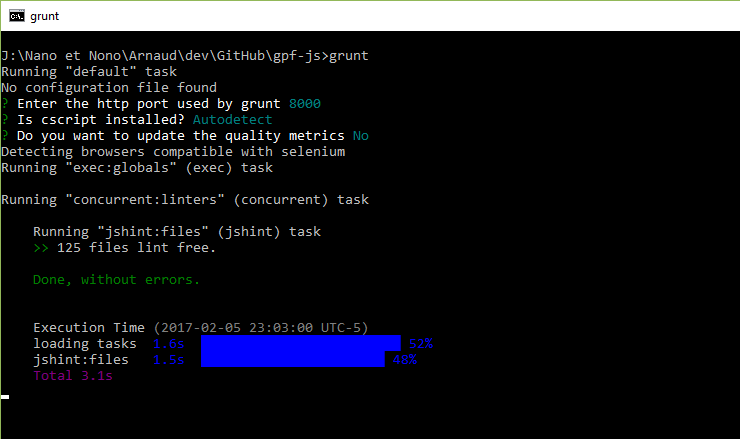

To make it a part of the build process, I installed grunt-jsdoc and configured two tasks:

- One 'private' to see all symbols (including the private and the internal ones)

- One 'public' for the official documentation (only the public symbols)

The default rendering of jsdoc is quite boring, I decided to go with ink-docstrap for the public documentation.

To make sure my jsdoc comments are consistent and correctly used, I also configured eslint to validate them.

jsdoc offers many aliases (for instance @return and @returns). That's why eslint allows you to decide which tokens should be preferred.

Finally, I decided to control which files would be used to generate documentation through the sources.json doc properties.

The reality

After fixing all the linter errors, I quickly realized that I had to do lot of copy & paste to generate the proper documentation.

For example: when an internal method is exposed as a public API, the comment must be copied.

- On one hand, the internal method must be flagged with @private

- On the other hand, the public method has the same comment but flagged with @public

function _gpfExtend (destination, source) {

_gpfIgnore(source);

[].slice.call(arguments, 1).forEach(function (nthSource) {

_gpfObjectForEach(nthSource, _gpfAssign, destination);

});

return destination;

}

gpf.extend = _gpfExtend;

This implies double maintenance with the risk of forgetting to replace @private with @public.

The lazy developer in me started to get annoyed and I started to look at ways I could do things more efficiently.

In that case, we could instruct jsdoc to copy the comment from the internal method and use the name to detect if the API is public or private (depending if it starts with '_').

jsdoc plugins

That's quite paradoxical for a documentation tool to have such a short explanation on plugins.

Comments and doclets

So let's start with the basis: jsdoc relies on specific comment blocks (starting with exactly two stars) to detect documentation placeholders. It is not required for these blocks to be located near a symbol but, when they do, the symbol context is used to determine what is documented.

var a;

function () {

return {}

}

Each valid jsdoc comment block is converted into a JavaScript object, named doclet, containing extracted information.

For instance, the following comment and function

function _gpfExtend (destination, source) {

_gpfIgnore(source);

[].slice.call(arguments, 1).forEach(function (nthSource) {

_gpfObjectForEach(nthSource, _gpfAssign, destination);

});

return destination;

}

generates the following doclet { comment: '/**\n * Extends the destination object by copying own enumerable properties from the source object.\n * If the member already exists, it is overwritten.\n *\n * @param {Object} destination Destination object\n * @param {...Object} source Source objects\n * @return {Object} Destination object\n * @since 0.1.5\n */',

meta:

{ range: [ 834, 1061 ],

filename: 'extend.js',

lineno: 34,

path: 'J:\\Nano et Nono\\Arnaud\\dev\\GitHub\\gpf-js\\src',

code:

{ id: 'astnode100000433',

name: '_gpfExtend',

type: 'FunctionDeclaration',

paramnames: [Object] },

vars: { '': null } },

description: 'Extends the destination object by copying own enumerable properties from the source object.\nIf the member already exists, it is overwritten.',

params:

[ { type: [Object],

description: 'Destination object',

name: 'destination' },

{ type: [Object],

variable: true,

description: 'Source objects',

name: 'source' } ],

returns: [ { type: [Object], description: 'Destination object' } ],

name: '_gpfExtend',

longname: '_gpfExtend',

kind: 'function',

scope: 'global',

access: 'private' }

The structure itself is not fully documented as it depends on the tags used and the symbol context. However, some properties are most likely to be found, see the newDoclet event documentation.

I strongly recommend running jsdoc using the command line and output some traces to have a better understanding on how doclets are generated.

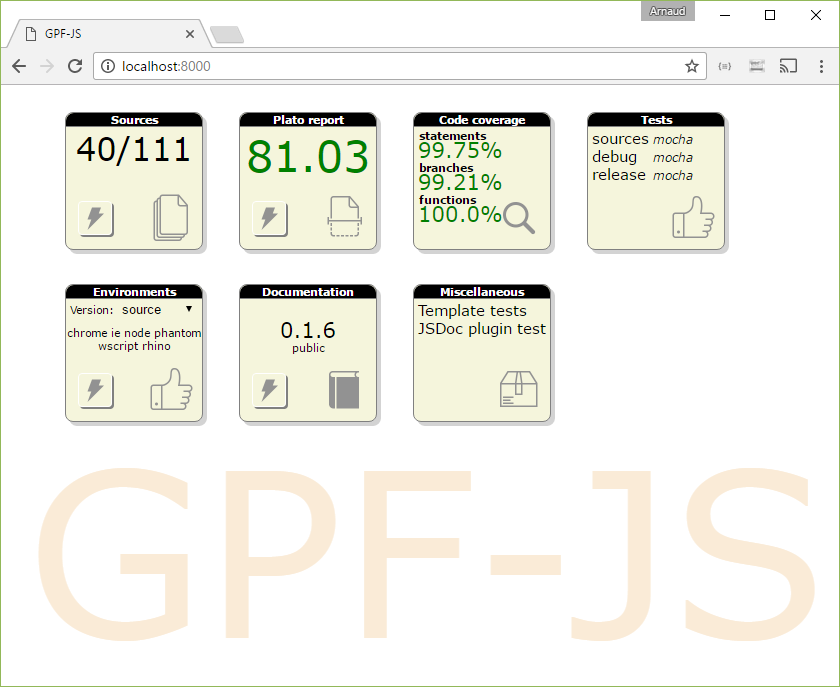

In the GPF-JS welcome page, I created a link named "JSDoc plugin test" for that purpose. It uses an exec:jsdoc task.

Plugins interaction

The plugins can be used to interact with jsdoc at three different levels:

- Interact with the parsing process through event handlers (beforeParse, jsdocCommentFound, newDoclet, processingComplete...)

- Define tags and be notified when they are encountered inside a jsdoc comment: it gives you the chance to alter the doclet that is generated

- Interact with the parsing process through an AST node visitor

The most important thing to remember is that you can interfere with doclet generation by altering them or even preventing them. But, I struggled to find ways to generate them on the fly (i.e. without any jsdoc block comment).

It looks like there is a way to generate new doclets with a node visitor. However, the documentation is not very clear on that part. See this example.

gpf.js plugin

Most of the following mechanisms are triggered during the processingComplete event so that all doclets are already generated and available.

Member types

When creating a class, I usually declare members and initialize them with a default value that is representative of the expected member type. This works well with primitive types or arrays but it gets more complicated when dealing with object references (which are most of the time initialized with null).

For instance, in error.js:

_gpfExtend(_GpfError.prototype, {

constructor: _GpfError,

code: 0,

In that case, the member type can easily be deduced from the AST node:

{ comment: '/**\n * Error code\n *\n * @readonly\n * @since 0.1.5\n */',

meta:

{ range: [ 801, 808 ],

filename: 'error.js',

lineno: 35,

path: 'J:\\Nano et Nono\\Arnaud\\dev\\GitHub\\gpf-js\\src',

code:

{ id: 'astnode100000209',

name: 'code',

type: 'Literal',

value: 0 } },

description: 'Error code',

readonly: true,

since: '0.1.5',

name: 'code',

longname: 'gpf.Error#code',

kind: 'member',

memberof: 'gpf.Error',

scope: 'instance' }

Indeed the AST structure provides the literal value the member is initialized with (see meta.code.value).

This is done in the _addMemberType function.

Access type based on naming convention

There are no real private members in JavaScript. There are ways to achieve similar behavior (such as function scoped variables used in closure methods) but this is not the discussion here.

The main idea is to detail, through the documentation, which members the developer can rely on (public or protected when inherited) and which ones should not be used directly (because they are private).

Because of the way JavaScript is designed, everything is public by default. But I follow the naming convention where the underscore at the beginning of the member name means that the member is private.

As a consequence, the symbol name gives information about its access type.

This is leveraged in the _checkAccess function.

Access type based on class definitions

In the next version, I will implement a class definition method and the structure will provide information about members visibility. This will include a way to define static members.

The idea will be to leverage the node visitor to keep track of which visibility is defined on top of members.

Custom tags

Through custom tags, I am able to instruct the plugin to modify the generated doclets in specific ways. I decided to prefix all custom tags with "gpf:" to easily identify them, a dictionary defines all the existing names and their associated handlers. It is leveraged in the _handleCustomTags function.

@gpf:chainable

When a method is designed to return the current instance so that you can easily chain calls, the tag @gpf:chainable is used. It instructs jsdoc that the return type is the current class and the description is normalized to "Self reference to allow chaining".

It is implemented here.

@gpf:read / @gpf:write

Followed by a member name, it provides pre-defined signatures for getters and setters. Note that the member doclet must be defined when the tag is executed.

They are implemented here.

@gpf:sameas

This basically solves the problem I mentioned at the beginning of the article by copying another symbol documentation, provided the doclet exists.

It is implemented here.

The enumeration case

The library uses an enumeration to describe the host type. The advantage of an enumeration is the encapsulation of the value that is used internally. Sadly, jsdoc reveals this value as the 'default value' in the generated documentation.

Hence, I decided to remove it.

This is done here, based on this condition.

Actually, the type is also listed but the enumeration itself is a type... It will be removed.

Error generation in GPF-JS

That's probably the best example to demonstrate that laziness can become a virtue.

In the library, error management is handled through specific exceptions. Each error is associated to a specific class which comes with an error code and a message. The message can be built with substitution placeholders. The gpf.Error class offers shortcut methods to create and throw errors in one call.

For instance, the AssertionFailed error is thrown with: gpf.Error.assertionFailed({

message: message

});

The test case shows the exception details: var exceptionCaught;

try {

gpf.Error.assertionFailed({

message: "Test"

});

} catch (e) {

exceptionCaught = e;

}

assert(exceptionCaught instanceof gpf.Error.AssertionFailed);

assert(exceptionCaught.code === gpf.Error.CODE_ASSERTIONFAILED);

assert(exceptionCaught.code === gpf.Error.assertionFailed.CODE);

assert(exceptionCaught.name === "assertionFailed");

assert(exceptionCaught.message === "Assertion failed: Test");

Errors generation

You might wonder how the AssertionFailed class is declared?

Actually, this is almost done in two lines of code: _gpfErrorDeclare("error", {

assertionFailed:

"Assertion failed: {message}",

The _gpfErrorDeclare internal method is capable of creating the exception class (its properties and throwing helper) using only an exception name and a description. It extensively uses code generation technics.

Documentation generation

As you might notice, the jsdoc block comment preceding the assertionFailed declaration does not contain any class or function documentation. Indeed, this comment is reused by the plugin to generate new comments.

Actually, this is done in two steps:

Creating new documentation blocks during the beforeParseHooking the beforeParse event, the plugin will search for any use of the _gpfErrorDeclare method.

A regular expression captures the function and extract the two parameters. Then, a second one extracts each name, message and description to generate new jsdoc comments.

Blocking the default handling through the node visitorBy default, the initial jsdoc block comment will document a temporary object member. Now that the proper comments have been injected through the beforeParse event, a node visitor prevents any doclet to be generated inside the _gpfErrorDeclare method.

This is implemented here.

Actually, I could have removed the comment block during the beforeParse event but the lines numbering would have been altered.

ESLint customization

Adding new function signature tags through the jsdoc plugin helps me to reduce the amount of comments required to document the code. As mentioned at the beginning of the article, I configured eslint to validate any jsdoc comment.

However, because the linter is not aware of the plugin, it started to tell me that my jsdoc comments were invalid.

So I duplicated and customized the valid-jsdoc.js rule to make it aware of those new tags.

@since

Knowing in which version an API is introduced may be helpful. The is the purpose of the tag @since. However, manually setting it can be boring (and you might forget some comments).

Here again, this was automated.

Conclusion

Bill Gates quote

Obviously, there is an upfront investment to automate everything but, now, the lazy developer in me is satisfied.

A ninja is a master of disguise. How do you apply the JavaScript ninjutsu to hide an object member so that nobody

can see (and use) it? Here are several ways.

A ninja is a master of disguise. How do you apply the JavaScript ninjutsu to hide an object member so that nobody

can see (and use) it? Here are several ways.

This new release introduces the interface concept and also prepares future optimizations

of the release version.

This new release introduces the interface concept and also prepares future optimizations

of the release version.

Release 0.1.6 of GPF-JS delivers a basic class definition mechanism.

Working on the release 0.1.7, the focus is to improve this implementation by providing mechanism that mimic

the ES6 class definition. In particular, the super keyword is replaced with a $super member that provides

the same level of functionalities. Here is how.

Release 0.1.6 of GPF-JS delivers a basic class definition mechanism.

Working on the release 0.1.7, the focus is to improve this implementation by providing mechanism that mimic

the ES6 class definition. In particular, the super keyword is replaced with a $super member that provides

the same level of functionalities. Here is how.