In this article, I would like to talk about a problem that is typical

whenever you have to deal with asynchronous APIs (such as AJAX requests):

how do you synchronize your calls to trigger an action when everything

completed?

In this article, I would like to talk about a problem that is typical

whenever you have to deal with asynchronous APIs (such as AJAX requests):

how do you synchronize your calls to trigger an action when everything

completed?

There are great tools to address this issue (such as promises) but I want to explore a different (and simplest?) path and talk about "multi-threading".

Promises

I already talked about promises and this is clearly one of the best solution to handle sequencing of events.

I also recommend reading this awesome presentation from Trevor Burnham: Flow control with promises

However, not all APIs are using promises and, sometimes, you have to be creative to workaround the lack of helpers.

NodeJS folder exploration

One example I recently came through was that I had to recursively list all files of a folder in order to find specific ones.

NodeJS exposes its file API in two flavors:

- Synchronous version (for instance: fs.statSync, fs.readFileSync)

- Asynchronous version (for instance: fs.stat, fs.readFile)

Synchronous version

Obviously, the synchronous version is easier to develop as you can use the result of each file API immediately after the call. This simplifies a lot the folder exploration function.

download var fs = require("fs"),

path = require("path"),

start = new Date(),

files,

key,

count;

function exploreSync(currentPath, result) {

"use strict";

var stat = fs.statSync(currentPath);

if (undefined === result) {

// Allocate result dictionary that will be passed to the sub calls

result = {};

}

if (stat.isDirectory()) {

// Folder

var list = fs.readdirSync(currentPath),

len,

idx;

len = list.length;

for (idx = 0; idx < len; ++idx) {

exploreSync(path.join(currentPath, list[idx]), result);

}

} else {

// File

result[currentPath] = fs.readFileSync(currentPath);

}

return result;

}

files = exploreSync(process.argv[2]);

console.log("Here we can use files dictionary:");

count = 0;

for (key in files) {

if (files.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

++count;

console.log(key + " " + files[key].length);

}

}

console.log("Count: " + count);

console.log("Spent " + (new Date() - start) + "ms");

You might notice that there is no result testing in the above example. It is because an exception would be thrown by nodeJS if an error occurs.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

While it is so easy to develop the algorithm with the synchronous APIs, why does nodeJS exposes asynchronous ones?

There is one main reason: you must remember that the JavaScript engine is mono-threaded. If you develop a nodeJS web server that needs - whatever the reason - to use the above exploreSync function, then your server won't be available to process any other request until the folder exploration is done. This is clearly bad and not scalable.

The asynchronous versions of the file APIs rely on a simple idea: file access is done by the operating system. While doing that, the JavaScript engine could be used to do something else!

As a consequence, asynchronous versions of the API allow time sharing and - somehow - simulates multi-threading.

Regarding error management, in the synchronous version, error management is done through exceptions. Even if it is my preferred way (as it simplifies the code writing), the same can't be applied in asynchronous node. Indeed, as the possible error is known only when the processing layer completes the operation, where would the exception be thrown? Instead, nodeJS provides the error information in the callback so that you can decide to handle it (but you must not ignore it).

Asynchronous version

download var fs = require("fs"),

path = require("path"),

start = new Date(),

files,

key,

count;

function exploreAsync(currentPath, result) {

"use strict";

if (undefined === result) {

// Allocate result dictionary that will be passed to the sub calls

result = {};

}

fs.stat(currentPath, function (err, stat) {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else if (stat && stat.isDirectory()) {

// Folder

fs.readdir(currentPath, function (err, list) {

var

len,

idx;

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

len = list.length;

for (idx = 0; idx < len; ++idx) {

exploreAsync(path.join(currentPath, list[idx]), result);

}

}

});

} else {

fs.readFile(currentPath, function (err, data) {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

result[currentPath] = data;

}

});

}

});

}

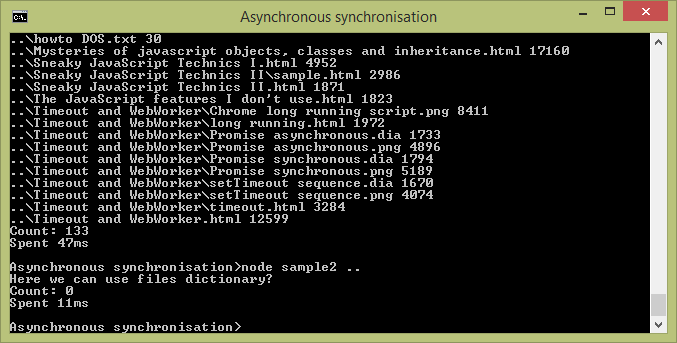

files = exploreAsync(process.argv[2]);

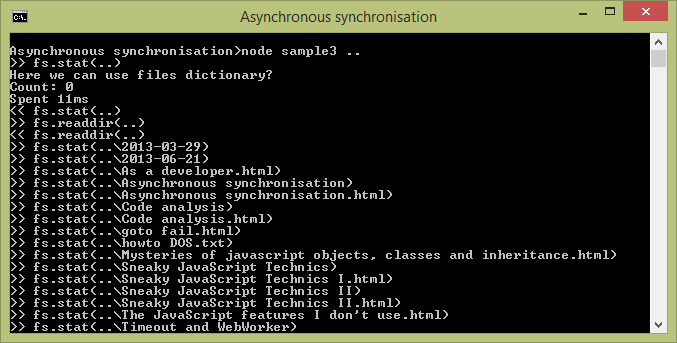

console.log("Here we can use files dictionary?");

count = 0;

for (key in files) {

if (files.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

++count;

console.log(key + " " + files[key].length);

}

}

console.log("Count: " + count);

console.log("Spent " + (new Date() - start) + "ms");

As you can see here, for each API used, a callback function is needed to receive the result as well as the error (if any).

Hold on a second, why don't I get any result?

Let put some traces...

download var fs = require("fs"),

path = require("path"),

start = new Date(),

files,

key,

count;

function exploreAsync(currentPath, result) {

"use strict";

if (undefined === result) {

// Allocate result dictionary that will be passed to the sub calls

result = {};

}

console.log(">> fs.stat(" + currentPath + ")");

fs.stat(currentPath, function (err, stat) {

console.log("<< fs.stat(" + currentPath + ")");

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else if (stat && stat.isDirectory()) {

// Folder

console.log(">> fs.readdir(" + currentPath + ")");

fs.readdir(currentPath, function (err, list) {

console.log("<< fs.readdir(" + currentPath + ")");

var

len,

idx;

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

len = list.length;

for (idx = 0; idx < len; ++idx) {

exploreAsync(path.join(currentPath, list[idx]), result);

}

}

});

} else {

console.log(">> fs.readFile(" + currentPath + ")");

fs.readFile(currentPath, function (err, data) {

console.log("<< fs.readFile(" + currentPath + ")");

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

result[currentPath] = data;

}

});

}

});

}

files = exploreAsync(process.argv[2]);

console.log("Here we can use files dictionary?");

count = 0;

for (key in files) {

if (files.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

++count;

console.log(key + " " + files[key].length);

}

}

console.log("Count: " + count);

console.log("Spent " + (new Date() - start) + "ms");

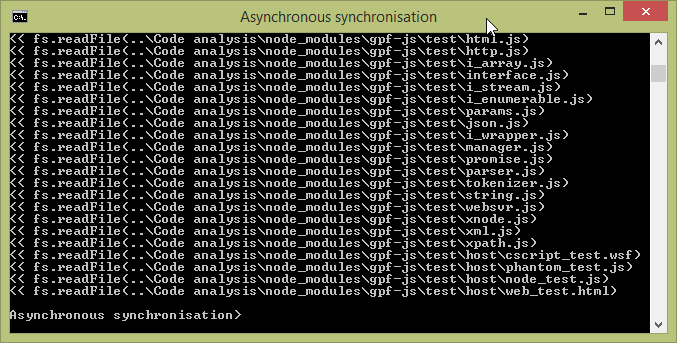

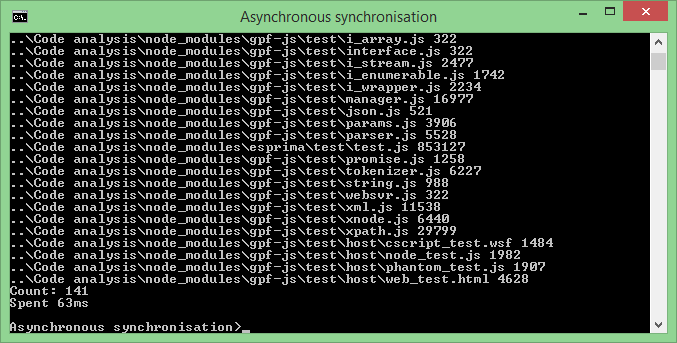

sample 3 (beginning) sample 3 (end)

sample 3 (end)

See? as those file API are asynchronous, the file dictionary is used before it is actually filled. But the filling does occur.

So the question is: how do you know the exploration ended?

The good old way

First of all, we will need to be called back when the function is completed. This changes the way the explore function is defined.

function exploreAsync(currentPath, callback, result) {//...

Then, we need to remember how many times we called an asynchronous API. Every time the associated callback is executed, we decrement this number. If we do it the right way, the number comes back to 0 when we have no more pending operation. As a consequence, it means that our job is done.

As a first step, I will use a global variable to represent this count: pendingCount.

download var fs = require("fs"),

path = require("path"),

start = new Date(),

key,

count,

pendingCount = 0;

function exploreAsync(currentPath, callback, result) {

"use strict";

if (undefined === result) {

// Allocate result dictionary that will be passed to the sub calls

result = {};

}

++pendingCount;

fs.stat(currentPath, function (err, stat) {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else if (stat && stat.isDirectory()) {

// Folder

++pendingCount;

fs.readdir(currentPath, function (err, list) {

var

len,

idx;

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

len = list.length;

for (idx = 0; idx < len; ++idx) {

exploreAsync(path.join(currentPath, list[idx]),

callback, result);

}

}

if (0 === --pendingCount) {

callback(result);

}

});

} else {

++pendingCount;

fs.readFile(currentPath, function (err, data) {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

result[currentPath] = data;

}

if (0 === --pendingCount) {

callback(result);

}

});

}

if (0 === --pendingCount) {

callback(result);

}

});

}

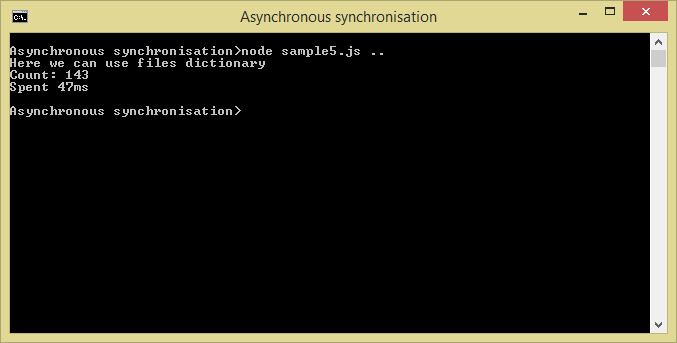

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], function (files) {

"use strict";

console.log("Here we can use files dictionary");

count = 0;

for (key in files) {

if (files.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

++count;

console.log(key + " " + files[key].length);

}

}

console.log("Count: " + count);

console.log("Spent " + (new Date() - start) + "ms");

});

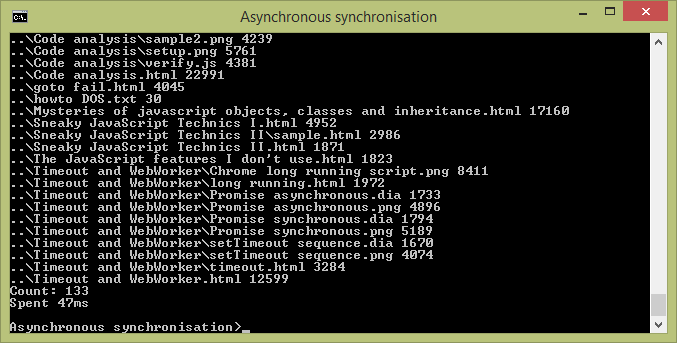

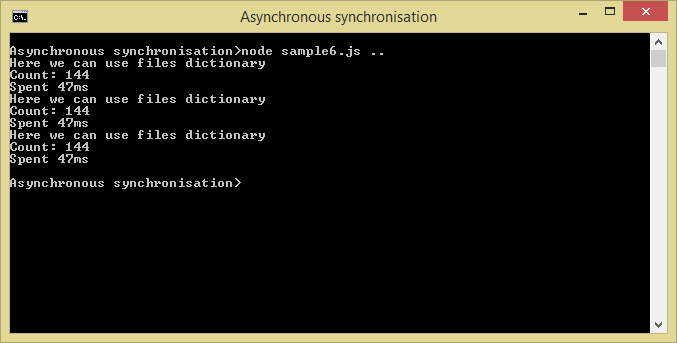

And... here we are !

The 'improved' good old way

So the pendingCount variable takes care of synchronizing the whole thing to trigger the end function when the algorithm completes. Great ! we have a non-blocking folder exploration function.

But... let see what happens if we try to call it more than once.

download /*...*/

function result (files) {

"use strict";

console.log("Here we can use files dictionary");

count = 0;

for (key in files) {

if (files.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

++count;

}

}

console.log("Count: " + count);

console.log("Spent " + (new Date() - start) + "ms");

}

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], result);

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], result);

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], result);

And the result is...

My callback function is called only once.

This is because the callback is triggered only when the pendingCount reaches 0 and this variable is global. Indeed, each explore execution is using the same variable.

So we must make sure to count those pending operation "privately" to each explore function call.

You might wonder why the pendingCount variable is not transmitted as a parameter like for the result list. JavaScript does not support passing scalar parameters (i.e. strings, numbers, boolean) by references (or pointer if you like). Hence, the value would be correctly transmitted but the updated one wouldn't be reflected in the caller. On the other hand, Object parameters (like the result list in our case) is transmitted by pointer. That's why we can update the list in the sub functions.

In the end, we have two solutions:

- Use an object that contains this number and transmit it as a parameter (could be a member of the result list)

- Create a closure that contains this variable as in a private scope

The second solution is implemented below:

download var fs = require("fs"),

path = require("path"),

start = new Date(),

key,

count;

function exploreAsync(currentPath, callback) {

"use strict";

var

result = {},

pendingCount = 0;

function _explore(currentPath) {

++pendingCount;

fs.stat(currentPath, function (err, stat) {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else if (stat && stat.isDirectory()) {

// Folder

++pendingCount;

fs.readdir(currentPath, function (err, list) {

var

len,

idx;

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

len = list.length;

for (idx = 0; idx < len; ++idx) {

_explore(path.join(currentPath, list[idx]));

}

}

if (0 === --pendingCount) {

callback(result);

}

});

} else {

++pendingCount;

fs.readFile(currentPath, function (err, data) {

if (err) {

console.error(err);

} else {

result[currentPath] = data;

}

if (0 === --pendingCount) {

callback(result);

}

});

}

if (0 === --pendingCount) {

callback(result);

}

});

}

_explore(currentPath);

}

function result (files) {

"use strict";

console.log("Here we can use files dictionary");

count = 0;

for (key in files) {

if (files.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

++count;

}

}

console.log("Count: " + count);

console.log("Spent " + (new Date() - start) + "ms");

}

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], result);

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], result);

exploreAsync(process.argv[2], result);

Conclusion

Whenever you have to deal with asynchronous operations, things are more complex (it's like multi-threading programming). But, JavaScript being mono-threaded, you don't have to care about simultaneous access to the same variable and, basically, any boolean / number variable can be used as a critical section.

Furthermore, this way of programming comes with interesting features:

- Non blocking calls (which means better user experience)

- Improved performances as you do things in parallel (check the time needed to explore the same folder 3 times)

Usually, it takes a big mind shift to come from the 'normal' sequential programming to this 'multi-threaded'-like way of doing things. But, then, you will discover a new playground that really worth the mind twisting. And, with small tricks and good practices, everything is possible.

As a technical support, I had to deal with situations where a quick and

dirty fix was necessary to get things done while waiting for the official

patch.

As a technical support, I had to deal with situations where a quick and

dirty fix was necessary to get things done while waiting for the official

patch.